what is the correct order of these ions, from largest to smallest?

2.8: Sizes of Atoms and Ions

- Page ID

- 36091

Learning Objectives

- To sympathise periodic trends in atomic radii.

- To predict relative ionic sizes inside an isoelectronic serial.

Although some people fall into the trap of visualizing atoms and ions as small, difficult spheres like to miniature table-lawn tennis balls or marbles, the quantum mechanical model tells u.s.a. that their shapes and boundaries are much less definite than those images advise. As a outcome, atoms and ions cannot be said to accept exact sizes. In this section, we talk over how atomic and ion "sizes" are defined and obtained.

Atomic Radii

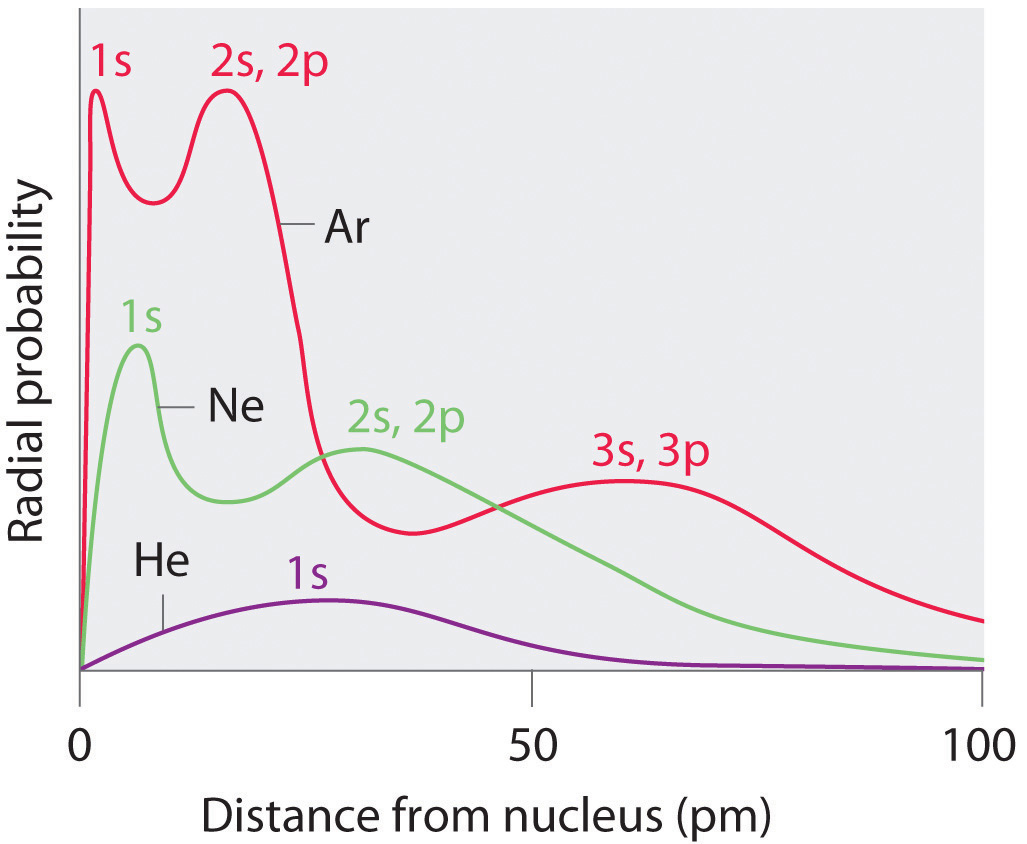

Recall that the probability of finding an electron in the diverse bachelor orbitals falls off slowly equally the distance from the nucleus increases. This bespeak is illustrated in Figure ii.eight.1 which shows a plot of total electron density for all occupied orbitals for three noble gases as a role of their distance from the nucleus. Electron density diminishes gradually with increasing distance, which makes it impossible to draw a abrupt line marking the boundary of an atom.

Figure 2.eight.1 likewise shows that in that location are singled-out peaks in the total electron density at particular distances and that these peaks occur at different distances from the nucleus for each chemical element. Each peak in a given plot corresponds to the electron density in a given principal trounce. Because helium has only one filled beat out (n = 1), information technology shows just a unmarried tiptop. In contrast, neon, with filled n = one and 2 principal shells, has two peaks. Argon, with filled n = 1, 2, and 3 principal shells, has iii peaks. The elevation for the filled n = ane shell occurs at successively shorter distances for neon (Z = 10) and argon (Z = 18) because, with a greater number of protons, their nuclei are more than positively charged than that of helium. Because the 1s ii beat out is closest to the nucleus, its electrons are very poorly shielded by electrons in filled shells with larger values of due north. Consequently, the two electrons in the n = 1 shell feel nearly the full nuclear charge, resulting in a strong electrostatic interaction betwixt the electrons and the nucleus. The free energy of the north = 1 shell likewise decreases tremendously (the filled is orbital becomes more stable) as the nuclear charge increases. For similar reasons, the filled northward = two vanquish in argon is located closer to the nucleus and has a lower energy than the n = ii trounce in neon.

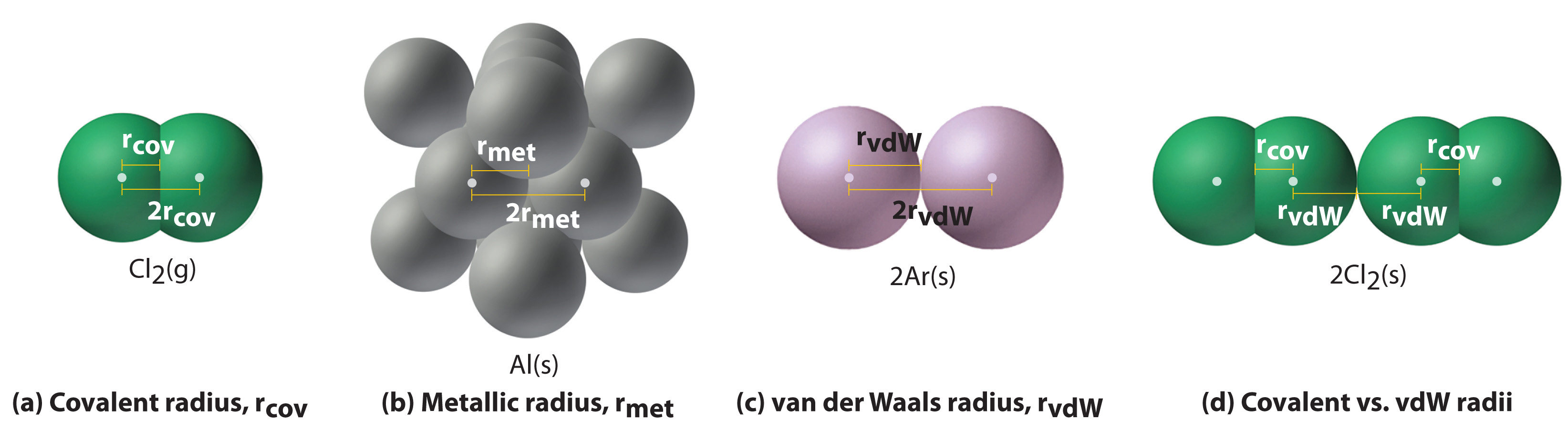

Figure two.eight.1 illustrates the difficulty of measuring the dimensions of an individual cantlet. Because distances between the nuclei in pairs of covalently bonded atoms can be measured quite precisely, however, chemists use these distances equally a ground for describing the approximate sizes of atoms. For instance, the internuclear distance in the diatomic Cl2 molecule is known to exist 198 pm. Nosotros assign half of this distance to each chlorine cantlet, giving chlorine a covalent diminutive radius (r cov), which is half the distance betwixt the nuclei of two like atoms joined by a covalent bond in the same molecule, of 99 pm or 0.99 Å (role (a) in Effigy ii.8.2). Diminutive radii are oft measured in angstroms (Å), a non-SI unit of measurement: 1 Å = i × 10−10 thou = 100 pm.

In a like approach, we can use the lengths of carbon–carbon single bonds in organic compounds, which are remarkably uniform at 154 pm, to assign a value of 77 pm as the covalent atomic radius for carbon. If these values practise indeed reflect the actual sizes of the atoms, then we should be able to predict the lengths of covalent bonds formed between different elements by adding them. For example, nosotros would predict a carbon–chlorine distance of 77 pm + 99 pm = 176 pm for a C–Cl bond, which is very close to the average value observed in many organochlorine compounds.A like approach for measuring the size of ions is discussed later in this section.

Covalent diminutive radii can be determined for almost of the nonmetals, simply how practice chemists obtain atomic radii for elements that do not form covalent bonds? For these elements, a multifariousness of other methods have been adult. With a metallic, for example, the metallic atomic radius (rmet) is defined every bit one-half the distance betwixt the nuclei of two side by side metal atoms (part (b) in Figure 2.8.two). For elements such equally the noble gases, about of which form no stable compounds, nosotros tin employ what is called the van der Waals diminutive radius (rvdW), which is half the internuclear distance between 2 nonbonded atoms in the solid (part (c) in Figure 2.8.two). This is somewhat hard for helium which does not form a solid at any temperature. An atom such as chlorine has both a covalent radius (the altitude betwixt the two atoms in a \(Cl_2\) molecule) and a van der Waals radius (the distance between two Cl atoms in different molecules in, for example, \(Cl_{2(s)}\) at low temperatures). These radii are generally non the same (part (d) in Effigy two.eight.two).

Periodic Trends in Atomic Radii

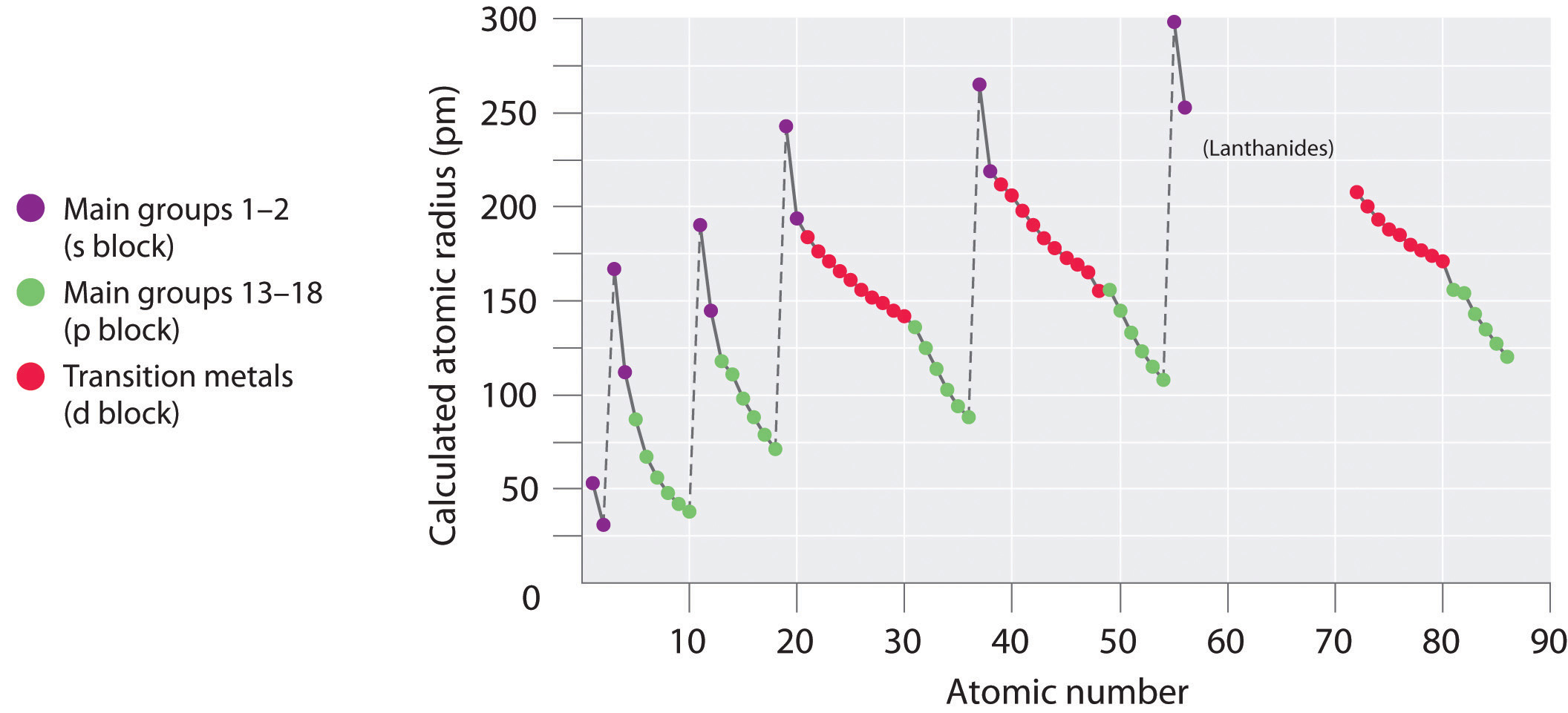

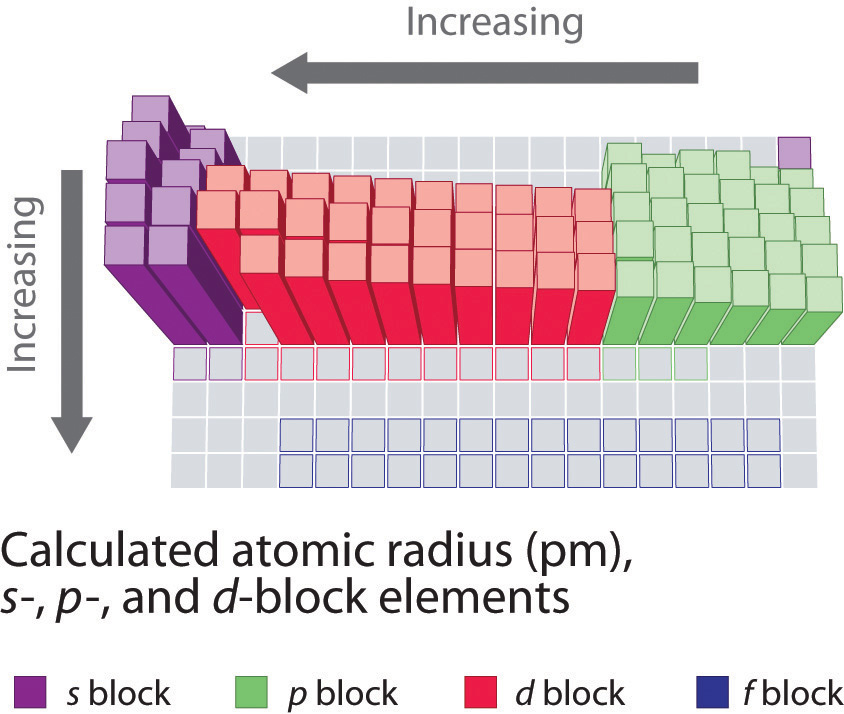

Because information technology is impossible to measure out the sizes of both metallic and nonmetallic elements using any ane method, chemists have adult a cocky-consequent mode of calculating atomic radii using the quantum mechanical functions. Although the radii values obtained by such calculations are not identical to any of the experimentally measured sets of values, they do provide a way to compare the intrinsic sizes of all the elements and clearly show that atomic size varies in a periodic fashion (Figure 2.8.3).

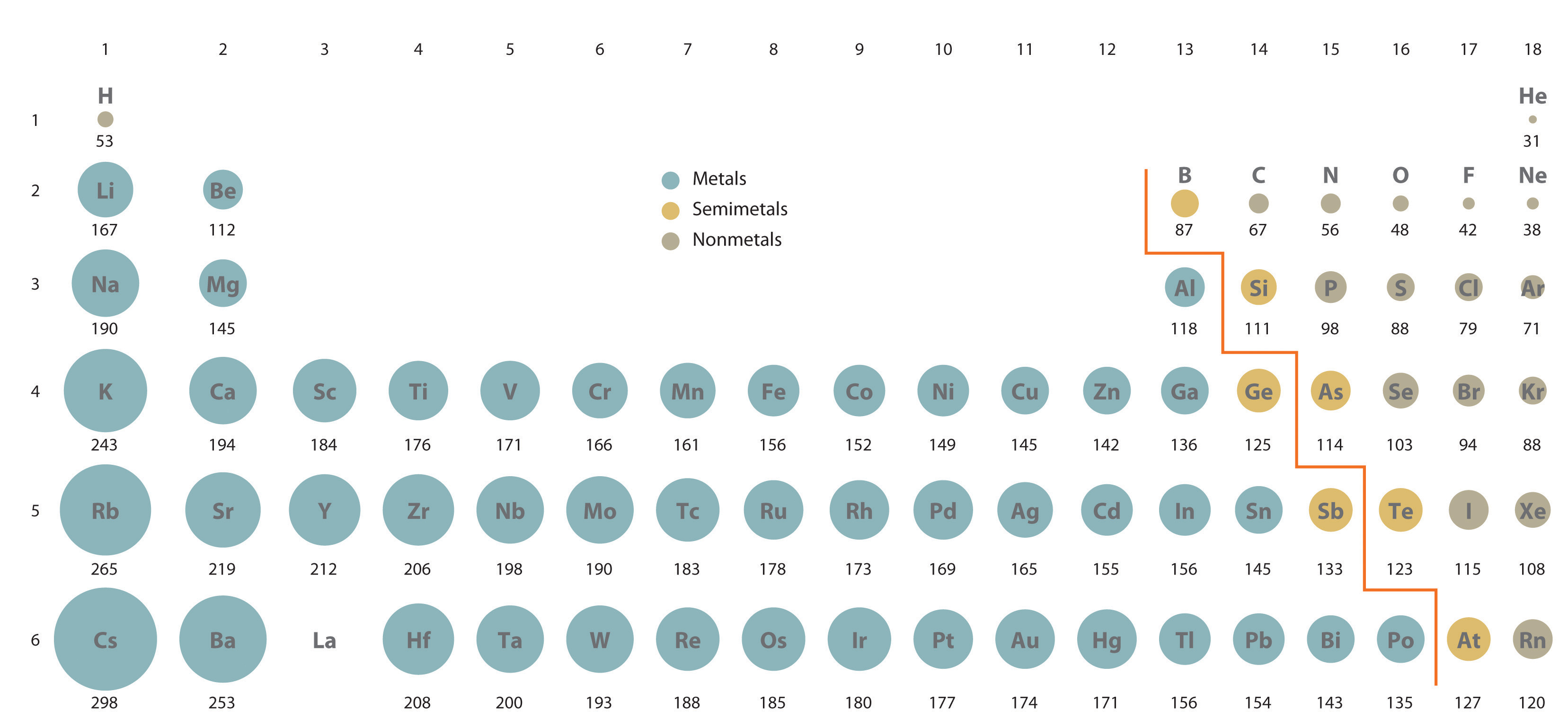

In the periodic table, atomic radii subtract from left to correct across a row and increase from top to bottom downward a column. Considering of these two trends, the largest atoms are found in the lower left corner of the periodic tabular array, and the smallest are found in the upper right corner (Figure 2.eight.iv).

Note

Atomic radii decrease from left to right across a row (a period) and increment from top to bottom down a column (a group or family).

Trends in atomic size result from differences in the effective nuclear charges ( Z eff ) experienced past electrons in the outermost orbitals of the elements. For all elements except H, the effective nuclear accuse is always less than the actual nuclear charge because of shielding effects. The greater the effective nuclear charge, the more strongly the outermost electrons are attracted to the nucleus and the smaller the atomic radius.

The atoms in the second row of the periodic table (Li through Ne) illustrate the effect of electron shielding. All have a filled 1southward 2 inner shell, but as we go from left to right across the row, the nuclear accuse increases from +3 to +10. Although electrons are being added to the 2s and 2p orbitals, electrons in the same chief shell are not very constructive at shielding one another from the nuclear charge. Thus the single 2southward electron in lithium experiences an effective nuclear charge of approximately +1 because the electrons in the filled 1s 2 beat out effectively neutralize two of the iii positive charges in the nucleus. (More detailed calculations give a value of Z eff = +1.26 for Li.) In contrast, the ii 2s electrons in beryllium do not shield each other very well, although the filled idue south 2 shell effectively neutralizes two of the four positive charges in the nucleus. This means that the constructive nuclear charge experienced by the 2southward electrons in glucinium is between +one and +2 (the calculated value is +ane.66). Consequently, beryllium is significantly smaller than lithium. Similarly, as we proceed across the row, the increasing nuclear charge is not effectively neutralized by the electrons being added to the twosouthward and twop orbitals. The result is a steady increase in the constructive nuclear charge and a steady decrease in atomic size.

The increase in diminutive size going down a column is also due to electron shielding, but the situation is more complex because the principal quantum number due north is not constant. As we saw in Chapter ii, the size of the orbitals increases equally n increases, provided the nuclear charge remains the same. In group 1, for example, the size of the atoms increases substantially going down the cavalcade. It may at starting time seem reasonable to attribute this effect to the successive addition of electrons to ns orbitals with increasing values of n. However, information technology is of import to remember that the radius of an orbital depends dramatically on the nuclear accuse. Equally we go down the column of the group 1 elements, the principal breakthrough number n increases from 2 to half-dozen, but the nuclear accuse increases from +three to +55!

As a outcome the radii of the lower electron orbitals in Cesium are much smaller than those in lithium and the electrons in those orbitals experience a much larger force of allure to the nucleus. That force depends on the constructive nuclear accuse experienced by the the inner electrons. If the outermost electrons in cesium experienced the full nuclear accuse of +55, a cesium atom would be very modest indeed. In fact, the effective nuclear charge felt past the outermost electrons in cesium is much less than expected (6 rather than 55). This means that cesium, with a 6s 1 valence electron configuration, is much larger than lithium, with a 2s 1 valence electron configuration. The constructive nuclear charge changes relatively piddling for electrons in the outermost, or valence shell, from lithium to cesium because electrons in filled inner shells are highly effective at shielding electrons in outer shells from the nuclear charge. Even though cesium has a nuclear charge of +55, information technology has 54 electrons in its filled 1southward 2twosouthward 22p sixiiisouthward ii3p 6ivs ii3d tenfourp 65s 24d x5p six shells, abbreviated as [Xe]vs 24d x5p vi, which effectively neutralize most of the 55 positive charges in the nucleus. The same dynamic is responsible for the steady increase in size observed as nosotros get downward the other columns of the periodic table. Irregularities can usually exist explained by variations in effective nuclear charge.

Annotation

Electrons in the same chief vanquish are not very effective at shielding one another from the nuclear charge, whereas electrons in filled inner shells are highly constructive at shielding electrons in outer shells from the nuclear charge.

Example 2.8.1

On the ground of their positions in the periodic table, adjust these elements in club of increasing diminutive radius: aluminum, carbon, and silicon.

Given: three elements

Asked for: adapt in order of increasing diminutive radius

Strategy:

- Identify the location of the elements in the periodic tabular array. Determine the relative sizes of elements located in the same column from their principal quantum number n. Then decide the order of elements in the same row from their effective nuclear charges. If the elements are not in the same column or row, employ pairwise comparisons.

- List the elements in social club of increasing atomic radius.

Solution:

A These elements are not all in the aforementioned cavalcade or row, and so we must use pairwise comparisons. Carbon and silicon are both in group 14 with carbon lying higher up, so carbon is smaller than silicon (C < Si). Aluminum and silicon are both in the third row with aluminum lying to the left, so silicon is smaller than aluminum (Si < Al) because its effective nuclear accuse is greater. B Combining the two inequalities gives the overall order: C < Si < Al.

Practise 2.8.1

On the basis of their positions in the periodic table, arrange these elements in gild of increasing size: oxygen, phosphorus, potassium, and sulfur.

- Answer:

- O < S < P < 1000

Ionic Radii and Isoelectronic Series

An ion is formed when either one or more electrons are removed from a neutral atom (cations) to form a positive ion or when additional electrons attach themselves to neutral atoms (anions) to class a negative one. The designations cation or anion come from the early on experiments with electricity which institute that positively charged particles were attracted to the negative pole of a battery, the cathode, while negatively charged ones were attracted to the positive pole, the anode.

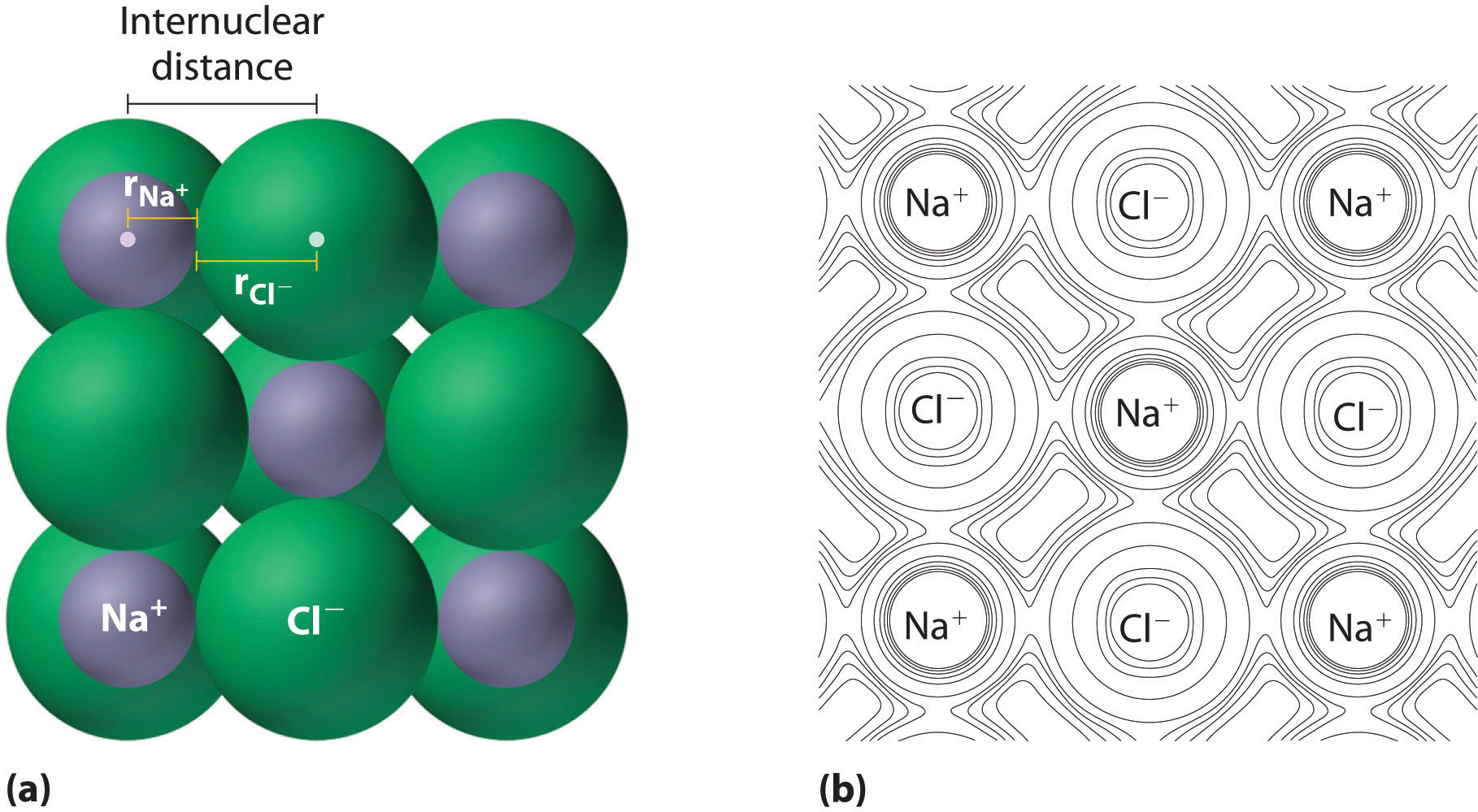

Ionic compounds consist of regular repeating arrays of alternating positively charged cations and negatively charges anions. Although information technology is not possible to mensurate an ionic radius directly for the same reason information technology is non possible to direct measure an atom's radius, it is possible to mensurate the altitude between the nuclei of a cation and an next anion in an ionic chemical compound to determine the ionic radius (the radius of a cation or anion) of one or both. As illustrated in Effigy 2.8.half dozen , the internuclear distance corresponds to the sum of the radii of the cation and anion. A multifariousness of methods have been developed to divide the experimentally measured distance proportionally between the smaller cation and larger anion. These methods produce sets of ionic radii that are internally consequent from 1 ionic compound to another, although each method gives slightly different values. For example, the radius of the Na+ ion is essentially the same in NaCl and Na2S, as long as the same method is used to measure it. Thus despite minor differences due to methodology, certain trends can be observed.

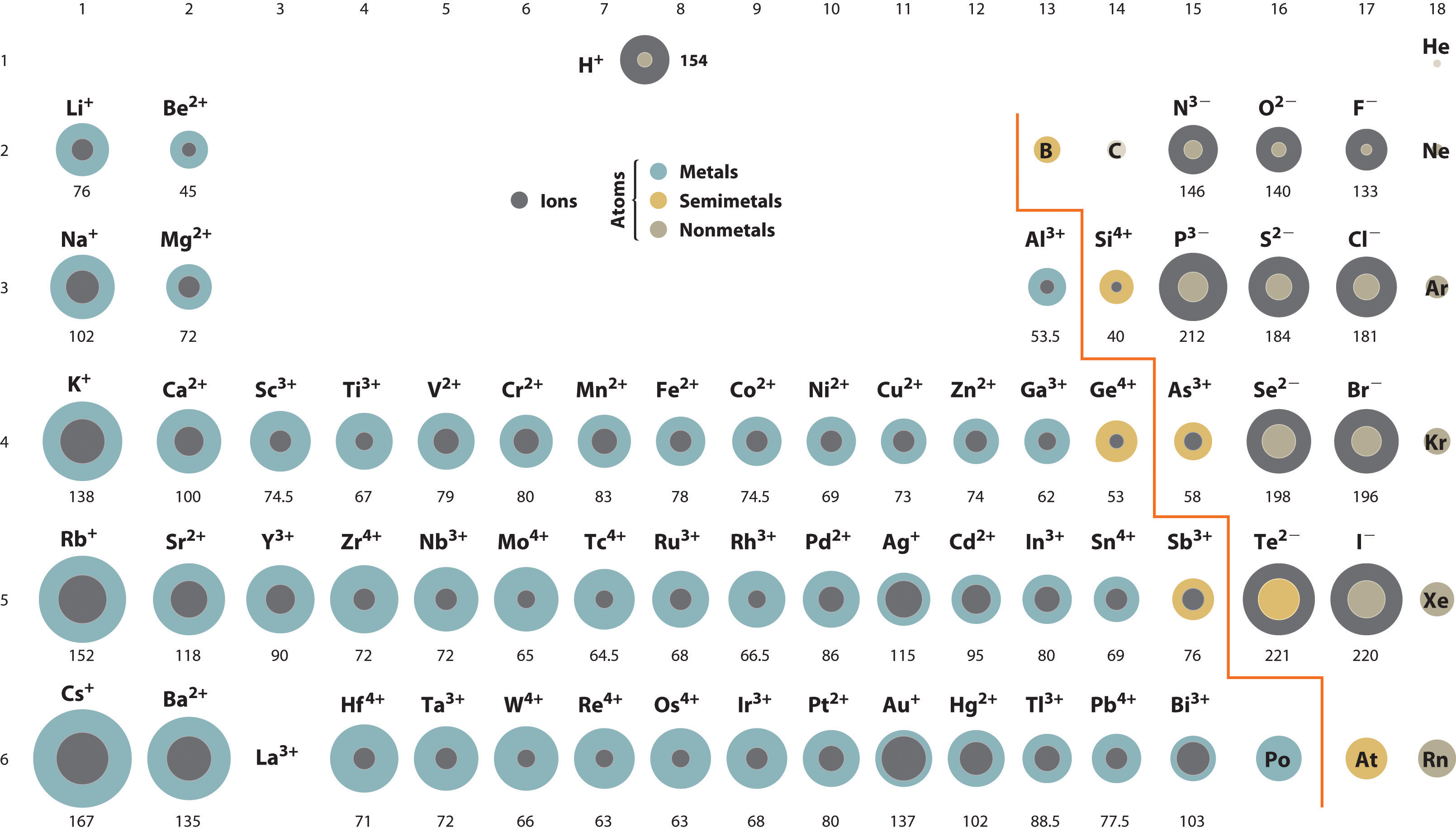

A comparison of ionic radii with diminutive radii (Figure 2.8.vii) cation, having lost an electron, is always smaller than its parent neutral atom, and an anion, having gained an electron, is e'er larger than the parent neutral atom. When one or more electrons is removed from a neutral atom, two things happen: (1) repulsions between electrons in the same principal shell subtract because fewer electrons are present, and (2) the constructive nuclear accuse felt by the remaining electrons increases because there are fewer electrons to shield one some other from the nucleus. Consequently, the size of the region of space occupied past electrons decreases (compare Li at 167 pm with Li+ at 76 pm). If dissimilar numbers of electrons can be removed to produce ions with different charges, the ion with the greatest positive charge is the smallest (compare Feii + at 78 pm with Feiii + at 64.five pm). Conversely, adding ane or more than electrons to a neutral cantlet causes electron–electron repulsions to increase and the effective nuclear charge to decrease, so the size of the probability region increases (compare F at 42 pm with F− at 133 pm).

Notation

Cations are ever smaller than the neutral cantlet, and anions are e'er larger.

Because nearly elements form either a cation or an anion only non both, at that place are few opportunities to compare the sizes of a cation and an anion derived from the same neutral cantlet. A few compounds of sodium, notwithstanding, comprise the Na− ion, allowing comparing of its size with that of the far more than familiar Na+ ion, which is found in many compounds. The radius of sodium in each of its three known oxidation states is given in Table 2.viii.1. All three species have a nuclear charge of +xi, but they contain 10 (Na+), eleven (Na0), and 12 (Na−) electrons. The Na+ ion is significantly smaller than the neutral Na cantlet because the iiis ane electron has been removed to requite a closed shell with n = 2. The Na− ion is larger than the parent Na cantlet because the additional electron produces a 3s ii valence electron configuration, while the nuclear charge remains the same.

| Na+ | Na0 | Na− | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electron Configuration | idue south iitwosouthward 22p 6 | 1s iiiis 2twop viiiis 1 | 1south 2twos ii2p half-dozen3s 2 |

| Radius (pm) | 102 | 154* | 202† |

| *The metal radius measured for Na(s). | |||

| †Source: M. J. Wagner and J. L. Dye, "Alkalides, Electrides, and Expanded Metals," Almanac Review of Materials Science 23 (1993): 225–253. | |||

Ionic radii follow the same vertical trend as atomic radii; that is, for ions with the same accuse, the ionic radius increases going downwardly a column. The reason is the same as for atomic radii: shielding past filled inner shells produces little change in the effective nuclear charge felt by the outermost electrons. Once more, principal shells with larger values of n lie at successively greater distances from the nucleus.

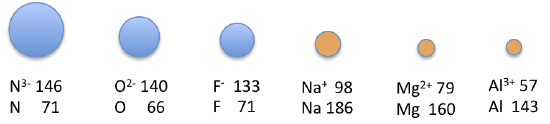

Because elements in unlike columns tend to grade ions with different charges, it is not possible to compare ions of the aforementioned charge across a row of the periodic table. Instead, elements that are adjacent to each other tend to form ions with the same number of electrons but with dissimilar overall charges because of their unlike diminutive numbers. Such a set of species is known as an isoelectronic series. For example, the isoelectronic series of species with the neon closed-shell configuration (onesouth 2iidue south 2iip half-dozen) is shown in Table 7.3

The sizes of the ions in this series decrease smoothly from Due northiii− to Al3 +. All half-dozen of the ions comprise 10 electrons in the 1s, iisouth, and twop orbitals, but the nuclear charge varies from +7 (Due north) to +13 (Al). As the positive charge of the nucleus increases while the number of electrons remains the same, there is a greater electrostatic attraction between the electrons and the nucleus, which causes a subtract in radius. Consequently, the ion with the greatest nuclear charge (Al3 +) is the smallest, and the ion with the smallest nuclear charge (Nthree−) is the largest. The neon atom in this isoelectronic series is not listed in Table 2.8.3, because neon forms no covalent or ionic compounds and hence its radius is difficult to measure.

| Ion | Radius (pm) | Atomic Number |

|---|---|---|

| N3− | 146 | 7 |

| O2− | 140 | eight |

| F− | 133 | 9 |

| Na+ | 98 | 11 |

| Mg2 + | 79 | 12 |

| Al3 + | 57 | xiii |

Example 2.8.2

Based on their positions in the periodic table, arrange these ions in order of increasing radius: Cl−, 1000+, Stwo−, and Se2−.

Given: four ions

Asked for: order by increasing radius

Strategy:

- Decide which ions grade an isoelectronic series. Of those ions, predict their relative sizes based on their nuclear charges. For ions that do not form an isoelectronic series, locate their positions in the periodic tabular array.

- Determine the relative sizes of the ions based on their principal breakthrough numbers northward and their locations within a row.

Solution:

A We meet that Southward and Cl are at the correct of the 3rd row, while One thousand and Se are at the far left and right ends of the fourth row, respectively. Thou+, Cl−, and South2− course an isoelectronic series with the [Ar] closed-shell electron configuration; that is, all 3 ions contain xviii electrons but have unlike nuclear charges. Because K+ has the greatest nuclear charge (Z = nineteen), its radius is smallest, and S2− with Z = 16 has the largest radius. Because selenium is directly below sulfur, we expect the Se2− ion to be even larger than Due south2−. B The gild must therefore be Yard+ < Cl− < Stwo− < Se2−.

Practice 2.viii.2

Based on their positions in the periodic table, adapt these ions in order of increasing size: Br−, Catwo +, Rb+, and Srtwo +.

- Answer:

- Ca2 + < Sr2 + < Rb+ < Br−

Summary

Ionic radii share the same vertical trend as atomic radii, just the horizontal trends differ due to differences in ionic charges.

A variety of methods take been established to mensurate the size of a single atom or ion. The covalent atomic radius ( r cov ) is half the internuclear distance in a molecule with two identical atoms bonded to each other, whereas the metallic diminutive radius ( r met ) is defined as half the distance between the nuclei of two next atoms in a metallic chemical element. The van der Waals radius ( r vdW ) of an element is one-half the internuclear distance between two nonbonded atoms in a solid. Atomic radii decrease from left to right across a row because of the increase in effective nuclear charge due to poor electron screening by other electrons in the same main shell. Moreover, atomic radii increase from top to bottom down a column because the constructive nuclear charge remains relatively constant as the master quantum number increases. The ionic radii of cations and anions are ever smaller or larger, respectively, than the parent atom due to changes in electron–electron repulsions, and the trends in ionic radius parallel those in atomic size. A comparing of the dimensions of atoms or ions that have the same number of electrons simply different nuclear charges, chosen an isoelectronic series, shows a clear correlation between increasing nuclear charge and decreasing size.

Source: https://chem.libretexts.org/Courses/Mount_Royal_University/Chem_1201/Unit_2._Periodic_Properties_of_the_Elements/2.08%3A_Sizes_of_Atoms_and_Ions

0 Response to "what is the correct order of these ions, from largest to smallest?"

Post a Comment